“Dead reckoning” popped into my head, or it dropped into my head, as phrases often do. Curious about the phrase and curious about my experience when a phrase does appear in my mind as if out of nowhere (what is going on?), I began to pull on the words idly. Idly, dreamily, in the way I sometimes pull on loose fabric threads in my clothing before I even notice that I’m pulling on them. Though I’m not sure of the result until I’m somewhere along the line of a thread pull, and though I may only become truly wakeful when a thread pull threatens the integrity of a fabric, I’m already committed to an outcome even as I’m idle. Already in a thread pull process, before I wake enough to know what I am up to. And most of the time, I can stay happily idle. Part of a larger than wakefulness background, idle thread pulls with decent enough results are easily forgotten, as never fully noticed. Disasters and nightmares, hyperboles and freakouts are more of what I notice, and what I remember. Disasters demand solutions, nightmares provoke awakening, but the background hum of ease asks for nothing, by seeming design. Ordinary, nothing to it, almost nothing to notice, I mostly ignore it.

Just another phrase that appeared in my mind, “dead reckoning” came like a bolt from the blue, except more slight than a bolt, less even than a spark. More akin to the cling of a very slight tribocharge, the static force that makes socks cling together and tiny sparks appear when they rub, it had something of an electric feel to it.

(By Sean McGrath. A photo of a cat with clinging bits of tribocharged styrofoam, like clinging bits of charged idiom in my mind.)

I enjoy listening for odd bits of ordinary language as they appear in my mind, and I take note of the qualities of words and images as I hear them or see them. Little phrases, little idiomatic bits of language, are as if ever floating in some other space, along with images, floating by at another register than practical wakefulness, a flow of dream thoughts and reveries. Obvious and ordinary, a humming flow of dream thoughts. The hum goes on, regardless. The qualities of that flow, though, are always changing, and the qualities that I pick up in my conscious or preconscious or whatever I might call it, always seem to take form in relationship to the feel of my waking state. Sometimes, if I shift my state, if I shift the qualities of my listening, the dream thoughts will take on different guises, shifting along a range from something of a command register to a koan register and back. If I’m listening for a voice, sometimes the inner voice will speak a command to simple action in stentorian tone. But, if I shift my inner stance of listening and soften my expectation, soften my energy, the voice will also shift and I will hear it make enigmatic and koan-like phrases.

Reading and meditating seem to prime me for noting many inner phenomena, phenomena of a range that I have never tried to tabulate. Christopher Bollas (A native of Laguna Beach California who studied anthropology and folklore and then became a child counselor, and then a psychoanalyst and writer) said recently in a public lecture that he has never seen anyone quite capture the everyday fact of what we all generically call “stream of consciousness”. Some writers at some times in some ways may have captured different aspects of what goes on in different minds at different times, but the diversity of states and qualities is vast, even in one mind. (I could sum up an entire project in a few words by saying that the variety of qualities and states in any mind at any moment has not been captured by anyone, and cannot be. If something like that statement is close to true then a simple question can follow from that: why and how is it that I tend to clobber my own inner diversity of states into one world only, into “single vision and Newton’s sleep”? There are good enough words that some writers use to explore the redundancy of adult ambulatory existence, of single vision prison, and one of them is “character”. Character analysis is a rich area of unfinished study; I’m going to swerve away from that for now. I’ll just leave the ordinary word “character” here as a placeholder to mark the space where I would like to, in the future, explore some of that.)

Sometimes, words break through with insistence, and one day “dead reckoning” appeared, a phrase in my mind, out of nowhere. It asked for nothing from me, had only a slight insistence to it, not quite an urge. I would have ignored it if I were not waiting, if I had not lowered my threshold as I was puzzling over something. Aimless puzzling set me up like a cat whose fur had rubbed against something in dry air, and now a little piece of tribocharged language was clinging to me. (Tribocharged: so under the threshold that autocomplete will forever try to turn it to turbocharged. Going to get redlined every time I use it. May it ever be so. Statistical trends in language use are another part of the rub of language. Trends push, as the margins pull. And dropping my threshold allows me to be aware of many of the pressures of language in more open ways. Leaves me more free to choose, to play.)

Something of the puzzling I have been doing about language must have tribocharged the phrase somehow. Friction, the feel of the rough of ordinary language, what Roland Barthes called the rustle of language, already gives every phrase a charge. But I also rub against language as it rubs against me, and the friction of that rubbing gives the words different charges at different times. (Tribology is the study of friction and its Greek root means “to rub”.)

Extended over time, and supported by the work, the long, patient efforts of a few oddball characters, my puzzling itself has become a curiosity of mine, dependent on time and receptivity. Precious time, more precious receptivity, and even more rare “drop threshold” listening. Less official than a conscious practice, drop threshold listening seems to wait for me, like the cats that wait until every person is at work or asleep to wander the neighborhood. (Cats seem to rule when no adults are around; ever about their own business, they seem only occasionally concerned with the purposes of others.)

Puzzling over what could only partly be the subject of any official business, on the trail of “ordinary language”, and thankful for all the help I have received in a seemingly endless labor, I’ve arrived at an embarrassed realization. I don’t have much to bring back from the threshold, not much that I have formally derived, not much that I might pass on. Though it may be of the nature of threshold work that not much can be brought back from it, I want to ask myself, nonetheless: what, if any, has been the value of all the puzzling and listening?

It’s been vital to me; I have grown. Something of what the writer Roland Barthes, quoting the poet and filmmaker Pasolini, called a “desperate vitality” has even emerged: my own personal heart change, unremarkable and invisible to the rest of the world. That’s something, to me. But what benefits have I derived that I might share in written form with others?

I don’t have a program, and I don’t have anything formal or even anything formally edifying to offer. No programs, no theories, no new models. (No new coaching models, no new therapies. Rest easy, reader. Nothing to teach here.) May it be a relief to whoever does peruse these words to not meet with another program. I find it so, as one of my aims is to travel lighter. To become more informal. If listening to the ordinary is my goal, and if listening has no form, then traveling lightly may serve, as a certain style of writing and thinking may also serve. And the style and the flow of what comes naturally to me as I listen to and puzzle over the ordinary, I can share. I can try to “live the attitude” in my writing and communicate with what Barthes might call “the right pitch” and the right feel.

Apart from putting care into the words, from the basics of copy editing, to using grammar that at least parses easily enough to native speakers of English, apart from covering the basics, I can also speak to the basics of my ethos and my aims in writing this newsletter. I aim to write in a way that is forgettable. To flicker in and out of your mind, for my writing to appear and disappear from view, to ramble in entertaining ways, in informally intelligent ways. And then to have my words drop from your mind entirely. More of an experience than edification, and not a finished or valuable artifact. Points to make and perspectives to offer, experiences to describe, words and insights as side effects of a labor, a need to investigate, that drive me. The investigations are of some value; for me, it’s been enlivening, life saving even. At the same time, in an odd way, the work has, as Wittgenstein wrote, “left everything in its place” without changing a thing. And that, “everything left in its same place”, is something I want to write about, a part of my thinking about the everyday. Epiphanies of the everyday, evanescent and fugitive experiences, evoked and then forgotten. Experiences that occur in a moment, and then recede again from view, like dreams, or mist. Perhaps only a slight feeling is left. Descriptions and evocations of an experience of evanescence, of a heightened sensitivity to what just was a moment ago and of what is appearing now. (I have an odd word for that, metalepsis, which I have not even defined. Not in the sense I use it with. Using an odd word without definition and trying to use it informally, I depend on your indulgence, or even your apathy if you feel that as you trip or skip past or through these asides. Roland Barthes, the author who inspired me here, loved apathy and he happily found good uses for “apathy”, a word worthy of recovery. Recovery of shades of meaning in common words as a lover’s game, a hitting of a right pitch or a fitting style, Barthes was a master in that.)

Using natural language language freely and loosely, something that I can carry with me everywhere I go, is mostly not a practice, not a discipline, not even an investigation, but more awkwardly if more accurately, “a getting to know.” (“getting to know” comes from Wilfred Bion, another oddball who tried to clear a space for intuitive curiosity, to clear a place for “the empty space” of “I’m not so sure”. The empty space, as he often said, that is so quickly, too quickly filled, may be another simple way of referring to an inner turn to listening to the ordinary.)

With an ethos of the ordinary in mind, I’ve dropped the word philosophy from my phrasing of “ordinary language”, just as I’ve dropped every other noun that would qualify my investigations for formal designation. No Ordinary Language Philosophy, it’s not that for me anymore, if it ever was. It’s not philosophy. And it’s most definitely not psychoanalysis. (I wonder what Adam Phillips is up to with his formal project of Ordinary Language Psychoanalysis? He seems to have taken his own project into a more informal approach of late, although not as informal as aspire to be. I’m not alone in saying a personal goodbye to formal discipline. Giving up on programs, letting go of institutional support, is something that braver souls than I have done many times before. Wittgenstein is a good example. The dogmatism that he later self-diagnosed as dooming his seminal Tractatus, in part, lay for him in the fact that the Tractatus had an implicit official program in it, one that he initially hoped to fulfill at a later date. In retrospect, he thought the program misguided from the start and he turned to “investigations”, not philosophy. Philosophical Investigations without finished philosophy.)

A relief, ease, and even joy of ordinary language: it's ever available. Elusive though, and strange, because of that availability. Easily everywhere present without thought or strain, somehow I'm still meditating on it all the while I'm using it. All day I’m meditating on it, or is it meditating me? A threshold experience, like breathing, or sensation scanning. Is it me or is my breath breathing me? Is it me speaking or is language speaking me?( Dropping my threshold is an art, an art to surrender to more than an art to practice, because dropping a threshold can also be a threshold and surrender may be used as another simple word for that. Ordinary language gets reflexively weird when I play with it.)

Embracing the polysemy of words, of many senses to the same words, of as many senses as I can set in play at once, is an embrace of a rough ground. Curious to see if I can communicate what I mean to myself or to others in simple and ordinary ways, using words in any ways that may emerge in any moment, I’m often surprised to see how much can be communicated in such simple ways. Embracing, as well, the way others are using the same words as I, but in different ways: I welcome any words, any way. And now, in thinking over my intuitive wayfinding in the rough and open seas of everyday language, of how I navigate my encounters with other people and my encounters with aspects of the social environment, with groups, large and small, in puzzling over how I do so, dead reckoning feels fitting to me.

Meditating on the late lectures on Roland Barthes, wondering over how he has become a kind of lodestar to me, a flickering fixed point in the sky over what seems a rough and open ocean, with no reference points, in a space without reference points, without any official designation or program, an analogy, from navigation, of a most simple means of navigation called “dead reckoning” came to me. It was partly an atmosphere, and partly a faith in my own intuition that lead me to meditate on Barthes, and it was something of my own interest in idiomatic language that must have pre-selected “dead reckoning” for me. But, I did not consciously ask it to appear. I didn’t follow any fixed path to arrive at it.

It seems a matter of personal taste, but there also seems to be a logic inherent to the process, there seem to be reasons that dead reckoning is a phrase that sticks in mind, that persists in time. Dead reckoning appeals, to me, as an idiom and an analogy, because, among concrete practices of wayfinding, it has an odd, archaic feel to it. It gives me pause. Appearing mostly now as the name of a rock band or a movie, it also sounds vividly grim or metal enough to cling to mind. As a phrase it has some of the qualities that I look for in ordinary language. And as a common enough phrase that points to an old practice, one no longer prone to idealization, it has been mostly cast on the rubbish pile of history. Surviving now only as humble vernacular, it lies dormant in the brain, until a moment arises for its recall or use. And it has playful, ironic, analogical, or even serious and practical uses: uses up to us in a moment.

The practice itself of dead reckoning is also similar to ordinary language as a practice. It takes painstaking work to master dead reckoning skills. The necessary skills then become intuitive and I can forget them. But they are still there, somehow, when I need them. That tacit feeling of something at the tip of my fingers: intuition.

Dead reckoning is a historically early means of navigation, of going somewhere by water, of maintaining a heading whilst traversing across some body of water in order to arrive safely and efficiently at a destination. A sometimes laborious way of calculating a current position along a path and in relation to a previous position, using a reading of speed, of direction, and of time, the practice needs some fix or point and something relatively stable or “dead in the water”. Some sense of position and some sense of direction. Simple, direct, basic. It is also performed intuitively by animals when they navigate through what we call instinct. Best of all, perhaps, dead reckoning is prone to constant error. We must know up front how error prone it is; from the start, it needs control. We know in our bones that it must be used with checks and balances; it requires training for it to be an effective means. After work, struggle, mistakes, it may become tacit or intuitive, but only after hard work. Something about navigating makes us do work up front, and the people who don’t feel the dread inherent in navigating often don’t make it back to port.

(Minotaure aveugle guidé par une Fillette dans la Nuit, by Picasso. Blind minotaur guided by a child under a star-speckled night sky.)

Darwin (in 1873) hypothesized that animals must use some means of “dead reckoning” to navigate on their journeys. It was a clever intuition on his part, one to be followed. And the disciplined study of animal navigation that followed his intuition, now known as path integration, has grown to vast proportions. An interesting phrasing itself, “path integration” has some of the value-neutral qualities of science; such neutrality may feel a relief in relation to painful and dreadful work. Stubborn and difficult problems, associated in practice with work and pain, are euphemism-washed and stripped of some of their color, fit more for study and generalization than for only painstaking direct experience. How did animals evolve such sophisticated means of dead reckoning over such long histories of painful and dangerous struggle? And how do the animal inheritors of ancient struggle seem to navigate now with such grace and ease? Instinct is a simple word for something enigmatic.

(By peterwchen. The desert ant is an expert navigator and it raises its gaster as part of its dead reckoning. Path integration is a euphemism for dead reckoning, one fitted to scientific study. The desert ant zig-zags across drifting sands without markings, and somehow it knows its way straight back home every time. It depends on dead reckoning for survival.)

Wayfinding, another word used for intuitive navigation, and a fine word, is an idiom, however, more easily prone to idealized use, as if it were something that only bushmen are fit for. Wayfinding, then, as a word, lacks some of the qualities that I’m look for in this meditation on everyday analogy. (Some recent discussions of wayfinding are heavily prone to idealization of peoples of yore, before GPS. One recent work even suggested that bush people “never get lost”, and that they know everything about their environs. Every bush baby, in these accounts, knows how to navigate in ways lost to us poor moderns. Country folk and bush people may, in fact, if seen in a less idealized light, be more accustomed to experiences of being lost. Not being in a rush may allow for an adjusting to error, may allow for a waiting long enough re-find a way. Been there. Got lost. Found ways to carry on. Accounts of Inuit hunters, who do get lost in snowstorms, and who barely live to tell their tales, appear more full of humor than of all-knowing omnipotence. Laughter seems to come easy when you live and die by your own means. A side benefit of having no large group or network to blame for one’s errors, one has to face them or not. Put face to face with one’s insufficiency, one’s dependence on conditions greater than one’s self, one has to adjust. I remain dependent, on humor, on good cheer and good luck, as well as good enough sense, even when apparently alone.)

“Dead reckoning” may also serve me well as an analogy for navigating encounter with intuitive sense, because it can seem naively archaic in a GPS world, even though it is still useful and even though it is the basis for extremely sophisticated forms of navigation that operate without external reference, or as nearly without reference as possible. Without reference to the networked satellite information of GPS systems, with dead reckoning, one can be independent, free of networks, free of large group institutions. One can be independent as an animal, as a bushman, or as a small group with only a compass and sextant, or even as a craft with a “Ring Laser Gyro (RLG) system that has counter-propagating laser beams and three orthogonal ring laser gyroscopes.” That last means of dead reckoning, using berylium gyroscopes and lasers, may be out of my budget and may be more appropriate to missiles or submarines, but I find its awe-inspiring sophistication comical in analogy. It takes a lot to be independent.

(By Sanjay Acharya, an inertial navigation control from the 1950s. Dead reckoning requires sophisticated control.)

This little ramble is itself something of an investigation for me, a meditation, or a series of investigations and meditations. In my ethos, in part an ethos that is local to this very ramble, I feel inclined to be informal. Not programmatic. I need to make my next adjustment, take another measure of my heading, and correct my errors as I move along. In that light, I will swerve slightly away from conclusion as I wrap this up. But what can I offer in replacement that will please me and you and satisfy some sense of purpose or order?

A bullet point summary would not fit an ethos nor fit an aesthetics of meditation on a practico-poetic means of navigation. I’m at a similar waypoint here to one that Wittgenstein was at when he declared that “ethics and aesthetics are one”, where the way is the means and ordinary language and its careful use is the way.

No five easy steps to mastering dead reckoning in stormy seas, there may, in fact, be no easy way to even passable skill. Given that, and adjusting to the heavy weather of real life, perhaps more enlivening than any easy way, what ordinary waypoints can I trace? I need worthy waypoints and means of navigating with them. With some experience and having developed a good enough means of navigating the basics of life with basic, independent sense, do I have anything to share or to offer that I could pass on about how to develop something of that capacity?

(Käpt'n Jonny Arndt uses a sextant to guide by fixed points along the horizon. photo by Seanavigatorsson Olaf Arndt)

Arriving at good enough questions as worthy waypoints, the value of investigations. Not solutions, but good enough questions, and means of questioning and wayfinding. Basic problems to navigate by with basic sense.

Physicist Richard Feynman revealed in his interviews that he could hardly remember the solutions and the names given to different solutions to the basic problems of science, but that if you gave him a problem, he could arrive at a way of reasoning about it, and perhaps even a mathematical formalism to describe it. The formalisms, the destinations, that he arrived at through his own means would match, as they must, the same ones that we might look up on Wikipedia. He arrived there, because he could, through his own independent means. Not a scholar, but a practitioner, he was not erudite and not a theory guy. Neither was he against erudition or against sophisticated memorization of history and nomenclature. The daughters of memory were, for him, only of lesser importance in his work as a thinker and physicist than the daughters of inspiration. Guided by basic problems and basic senses in thinking about math and physics, to all accounts, he navigated quite well.

Feynman, charming and independent minded, can serve as an example and a kind of model, if I backpedal on some of the idealizations that can attend to the word “model”. To be so independent minded is to be dependent on something other than previous experience only, whether tribal or personal, whether on histories or vocabularies, or erudition or memorization. Feynman, like any good sailor, remained dependent on something if not on institutions and networks; he was guided by basic problems and basic good sense, by basic intuition and basic reasoning. Guided by intuition and control, he could go it alone only because of a dependence on “facts” where and when controls are available. He is a model, in that sense, of independence of mind.

But he is no ideal fit for all of us, just as an Inuit hunter is no universal ideal, nor is a Roland Barthes, nor a Wilfred Bion, nor an open ocean sailor. Without idealized figures to emulate, leaving such figures to epic tales or works of fiction, to models or dreams, how to navigate?

I return again to what started the ramble, to what prompted an old forgotten phrase. Zig-zagging like a desert ant under the hot sun, I have some sense of home, a very basic sense that seems not worth talking about, one that is no achievement. Basic sense, I have. Okay. And I also have some very basic problems in living. Those are steady. I can rely on them for problems if not solutions. Sophisticated instruments, institutions and networks can break down and their vocabularies may not translate well when my concern is the everyday. Yesterday’s solutions may be liabilities today.

I need something simpler than yesterday’s solutions, something closer to me than only the achievements of others. Take enough away and I am happy to just survive. Throw enough at me and I am happy to just make it through. But, making my way through my relatively unadventurous existence during an ordinary day in civilized society as an ordinary ambulatory adult, as just a man in a Sophocles kind of way? How do I do it? How does anyone? A question that I ask myself, still, after all the years.

I do have and still seem to need ideals, if in a kind of de-idealized sense, and I do use works and figures as fixed stars or guides, as references, as I seek to make my way. That seems ordinary, even obvious, but I puzzle over it. Why and how do a few works and figures still guide me?

Sailing the unknown, the open ocean far from any shore, fills me with dread. Something close to vertigo, I feel hesitant and careful in simply trying to keep standing when in open spaces, as if I’d like to reach for a railing if one were present, or a helping hand. But the hand that was there is gone, the shore that was still in sight a moment ago is out of view, and I feel wobbly. I’m brought close to my self, thrilled, anxious, and awake. Not sure if I’m going to make it, not sure of my position, but with a sense of my heading, with some stars in a night sky or with the sun in the day to guide me, I carry on.

No one hits the open ocean for pleasure. No one of old sailed past the pillars of Hercules without great risk; the pillars of Hercules were the ne plus ultra of the ancient mediterranean, the “nothing further” from which there was no way back. Only a few did so sail, and most of them never survived the effort; they were more likely to be fools than idealized heroes for others to follow. One had to feel the itch, to be impelled to it, a purely elective affinity. And when one no longer has any site of shore, no rocks, nothing dead in the water to navigate by, one only has the sun or a lodestar to dead reckon by. But, a lodestar is an error prone and dangerous thing to navigate by, and one uses a lodestar for navigation only if no other means is available. That’s the rub.

These works that still guide me are not an ideal but are still usable “as if” an ideal when I need something to make my way, to measure my progress, however poorly, in a space with no horizontal reference points. Real people, real works, mostly unfinished works, or projects with no end, do guide me. “How could anyone finish sailing the unknown?” A few works guide me in “dead reckoning” not because they reached solutions but because these works made their ethos an open-ended struggle with problems. And they serve me because the tentative answers that they arrive at seem only to serve to set them to further problems. In ocean open sailing, no solutions or achievements can guide me. The achievements of others and the finished artifacts of the social world seem more like starters for first learning how to sail; they don’t serve me as well when problems are more pressing and when my life is on the line. When the time for learning is over, and when I have to make use of what I have, it’s a struggle with real problems that still guides. I need a view of the problems now more than I need to memorize old solutions.

Guiding by problems or trying to add to my problems sounds a little odd. It’s not something I would ever suggest to anyone or coach anyone in. I mostly hear clamor for solutions. Fixes. Cures. (A simple analysis of the training corpus of the big LLMs can give you the weighted preference for solutions, promises, and cures over problems or pain. How often do I hear someone say that they need another problem?)

But I do see a move away from “cure” or a return to the reliability of the problem in a few oddballs. Both Bion and Wittgenstein took heart in adding to their problems. They gave up programs set to be fulfilled at some later date and they guided by the assurance that the seas would be rough and uncertain. How odd is that? “Making the best of the tough job of real life” is a Bion way of putting it. It makes sense to me, but it may not make sense to many. And I get it. I’m not proud of it in any way, nor do I want to coach, cajole or teach anyone to give up on the “cure”. I only approach the attitude of a Bion because it allows me to carry on with what I suspect is something close to the attitude that allows an Inuit hunter to wait out a snowstorm long enough to get some sense of the way back home. How does a desert ant makes its way back home in a sandy world with no reference points? A question to keep investigating by, where explanations are always tentative.

Barthes, at the end of his life, struggled mightily to sail past the pillars of dogma. And his last lectures do serve me as a kind of polestar in what has been a personal heart change, to what has become my own good-bye to dogma. (I’m only going to gesture to the late Barthes here and not explain any of the content.) The late lectures, like everything Roland Barthes, are sprawling, ungainly, rich and varied. There seems no easy way to sum his lectures up: no easy way to conclude them. And that is another part of what guides me; it’s very open ocean in form. In wondering over what I find so compelling about his investigations, and in puzzling over how I have begun to live in his lectures, to peruse them at random and hang with the notes and references, I’m hitting my own open seas. There are so many notes and references in The Neutral, endless notes. Barthes is, in these lectures, not someone to emulate; it’s not like that. He had his own style. I have mine. You have yours. He struggled, and his struggle with genuine problems I can follow, zig-zaggingly, in my own way, on other courses than him.

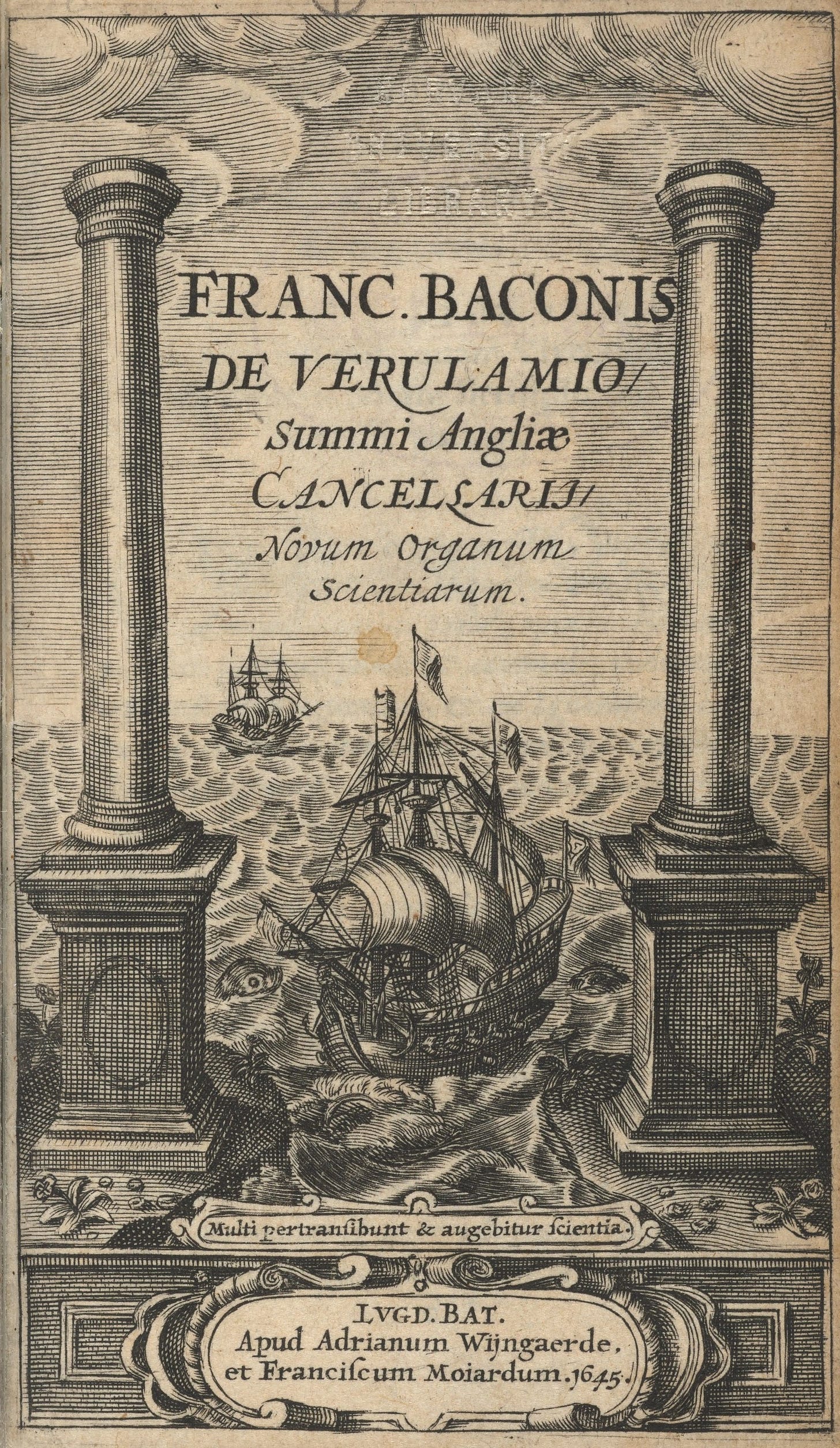

(The engraved title page to Francis Bacon’s Instauratio Magna, "Great Renewal”. Unfinished, its motto is Multi pertransibunt et augebitur scientia ,"Many will pass through and knowledge will be the greater" How many pass through the pillars of horizontal waypoint and at what risk? How many do so without anyone else ever noticing? Other problems, like how to carry on safely, can become more important than notice.)

Still thinking about how I’m guided, dependent on a few reference points in open seas, after years of life and experience, even after hell, is part of what leads me to meditate on dead reckoning as good enough analogy.

The weirdness of even trying to describe how a forgotten phrase appears casually in the mind entangled me immediately in analogy: I can say, as I did earlier, that a phrase “popped” or dropped into mind. And the visual metaphors used in common vernacular to describe entries of thoughts into the mind are easily passed over. But, thinking about the analogies embedded in such common forms is a good enough place for me to pause and puzzle over analogy. Analogy, Aristotle’s highest art, and Roy Wagner’s basis for “human invention” and the “invention of culture”, is key to this meditation of mine. How to use analogy, how to play with it, how to grow the capacity to play with it, and how to become aware of it’s ever-presence, conscious and preconcious? Analogy or good use of it, requires some creativity or some cleverness and it depends on reality or failure or suffering for its proving ground. Analogy thrives in the rough ground of ordinary language and ordinary experience, in vernacular. (Analogy, obvious and ordinary, keeps happening without conscious effort, in the conscious and preconscious of the mind. Part of the inevitable play of language and of the mind itself, analogy often needs more of checks and balances and testing than it does of naked stimulation. In like fashion to quantum computing, the reigning in of analogy by control—by “logic, common sense, induction, deduction”—is necessary for any working calculation to be made. Roy Wagner, an anthropologist, my friend and my professor made a life of playing with analogy. Some affinity must have kept me at his odd works long enough to begin to play a little, in my own ways, with it.)

It helps to get my ass kicked by stormy weather. It helps me to suffer, to tolerate a careful and sprawling, baffling writer like Roland Barthes. I get lost in Barthes, as I get lost in Bion, or in Wittgenstein. And there are others I get lost in, so many others. This short list is only arbitrary and suited to the local conditions of this one meditation now.

I hear no call here to start a new program, no battle call to save the right side of the brain. Sailing the unknown is too practical and immediate for any program, and its too demanding to be a compulsion that I would lay on any other person. Large group battles and mobilizations are better suited to other tasks than open ocean voyaging. (Funny how so many of the efforts to recover the right brain are so left brain in style. I ask myself why I feel a need for weighty tomes. Is it in order to validate my own feeble intuition? Or is it because I find rich sources of analogy in the sciences? It feels free and light to keep analogizing. And everything can be grist for the mill of it.)

All I hear now is my own breathing, a light breeze flapping the sails, and a few sea birds calling in the distance. Distant, guiding stars flicker in a dark sky. I can see a different view of the same facts, the same world as I was in a moment ago. And no one else needed to change, no one needed to join me. No groups. No institutions. When I guide by my own lights, however dim they feel, I can begin to hear my own heart beat. What can seem distant, what can seem lost, intuition and reason both, are, by my own lights, right here. Right here and nothing has changed. Same ordinary day. Same late day.

Barthes’s late, last aim was to “baffle the paradigm”. Wittgenstein said with perfect sincerity that he wanted to “add to the problems”. In the light of seeking problems more than solutions, in light of enhancing my awareness of pain, in adding to my burden, the current social prevalence of paradigms and technologies may, luckily, “add to the problems”. Wittgenstein would be happy. Ever more paradigms to baffle, more burdens to bear. More and more paradigms, more and more burdens. No lack in sight. Good news. Heavy weather.

Baffled again. I’ve lost my way repeatedly, even in this little sprawl of mine. This rambling preamble may be only a long roll of confused noise and thunder after a lightning flash that came to me as I puzzled over Roland Barthes. My oddball. My severe and harassing devil. Again, I never seem to tire of asking (though my reader may): why do I feel guided by his star? Clear and distinct to me, in my mind’s eye, a guide but not a model, and nothing to emulate, not an ideal, but still somehow a star in my firmament? How to even begin to explain that? And could I do it without falling into an idealization of Barthes as a “great figure”? I did begin. I did ramble. Enough or too much. I hardly started cover some of the ground that Barthes does. Another time, perhaps.

One final and simplest sense of dead reckoning comes into view as I struggle to end, to wrap up. Dead reckoning can refer to any “process of estimating the value of any variable quantity by using an earlier value and adding whatever changes have occurred in the meantime”(Wikipedia). Here I am at a most uncertain point of attempting to reckon any degree of any change at all, with whatever observations of change I am capable of. A good place to end or start.

Bion concluded his ambitious published works with an error prone and uncertain practice: to focus on the changes visible only within one hour of encounter with one other person. That was his highest and last art. It left quite a few people flummoxed and some disappointed. Not a theory. Not an explanation. But something more simple and something, to purposively use an ugly wording, impossible to operationalize. Destined to be thrown on the rubbish pile before anyone even took it up, it’s left to a stubborn, unproud few to use. Almost ridiculously simple on its face, and nothing original, it is similar to some of the practices of the contemplative mystical traditions.

To drop everything, to forget as much as possible the past and to not anticipate any future, in order to observe whatever changes or shifts are occurring now. Dead reckoning pure. Uncertain. In order to arrive at a more uncertain place than before. In order to observe a change. A worthy aim. He referred to this most basic observation of change, in the subtitle from his second to last major work, Transformations, with four simple words: from learning to growth. Simple words. Simple enough for anyone. Evocative enough for me.

Spot on. Lulling like lifetimes of half dreamed visitations in one Sunday afternoon nap.

Dread Reckoning reminds me of this cheeky old guy:

“The whole secret lies in arbitrariness. People usually think it is easy to be arbitrary, but it requires much study to succeed in being arbitrary so as not to lose oneself in it. One does not enjoy the immediate, but something quite different which he can arbitrarily control. You go to see the middle of a play, you read the third part of a book. By this means you insure yourself of a very different kind of enjoyment from that which the author has been so kind as to plan for you. You enjoy something entirely accidental; you consider the whole existence from this standpoint; let its reality be stranded thereon. I will cite an example. There was a man whose chatter certain circumstances made it necessary to listen to. At every opportunity he was ready with a little philosophical lecture, a very tiresome harangue. Almost in despair, I suddenly discovered that he perspired copiously when talking. I saw the pearls of sweat gather on his brow, unite to form a stream, glide down his nose, and hang at the extreme point of his nose in a drop-shaped body. From the moment of making this discovery, all was changed. I even took pleasure in inciting him to begin his philosophical instruction, merely to observe the perspiration on his brow and the end of his nose.”

–Kierkegaard

I love this humble attempt to mark out a few waypoints in the vast sea, by which to continue on finding more problems, getting lost and found again. Wonderful!